Mendeleev

While

in St. Petersburg we decided to try to find Demitri Mendeleev's

laboratory. He was the scientist who had discovered the

periodic

table which brought order to the science of chemistry. While

we

were on a driving tour of the city our guide pointed out Mendeleev's

statue outside the the university where his lab was located.

We

had no problem finding the building again when we were on our

own.

Now our problems began. There were no signs indicating where

the

lab was in the building. Actually it was a complex of

university

buildings with no signs on any of them. We asked someone who

was

passing by. We of course couldn't ask in Russian and they

didn't

speak English. They did understand us well enough to lead us

to a

door in a dark hallway which we had walked past in the first building

we entered. They pointed to the unmarked door and

left. We

tried the door. It was locked. Not knowing quite

what to do

we were standing there when Nancy noticed what appeared to be an ornate

doorbell button that had been painted over many times. We

tried

it and heard a bell ringing inside. The door soon

opened

and we were met by a woman who of course spoke to us in

Russian.

We indicated we didn't understand. She said

"Francais?" We said "Niet, English." She

said

"Deutsch?" Again niet. She tried a couple more

languages

then shrugged, said something we took to be "Sorry." and began to close

the door. We protested and pointed out the shirt and socks I

was

wearing (both had a copy of the periodic table) and asked if we could

just look around. She gave a little laugh and ushered us

inside.

We found ourselves in a rather small museum which had been his lab and

office. As we started to look around she pointed out a

picture on

the wall and named the people in it. They were scientists

that I

had heard of so I nodded and apparently looked like I

understood. So began our tour narrated entirely in

Russian. There are a remarkable number of technical words

that

when said in Russian sound like English spoken with a strong Russian

accent. That, plus being able to recognize equipment and

materials Mendeleev used, a lot of gestures, and her patience with us

resulted in a very educational and enjoyable tour. I

shouldn't

leave you with the impression that we understood everything

though. At one exhibit our guide, apparently

encouraged by

our interest, launched into an extended discourse. I was

straining to pick up something which I recognized. She could

see

that I wasn't getting it and tried again, and again, and

again. Finally Nancy 's eyes brightened as she said

"Ahhh!" As we were lead to the next exhibit I asked Nancy

what

our guide had said. Nancy replied very quietly that she had

no

idea but it was clear that our guide was going to keep explaining till

we understood and that was the only way we would see the rest of his

lab.

This statue wasn't far from his lab but we would have been looking for

a long

time if

that was our only clue to its location. The wall

next to

the statue displayed the periodic table of the elements. The

symbols for the ones he predicted would be discovered are shown in blue.

Here is our guide

pointing out

Mendeleev with some of the famous scientists of the day. The

second picture shows him with some of his students. In the

last

he is at his lab desk pondering the puzzle of how to make a logical

arrangement of the 63 elements that were then known.

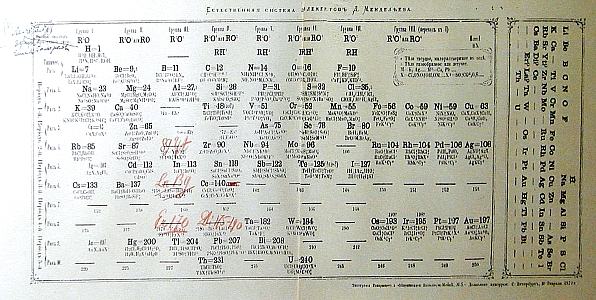

Here are several of the

periodic

tables that were on display. If you look closely at the first

handwritten one you will see chemical symbols and atomic

weights.

Note the question marks next to some entries. If there is no

chemical symbol it indicates his predicted weight for an element yet to

be discovered. Much has been made of those

predictions but

what is as impressive to me is the symbols and weight pairs he

questioned. Those question marks were saying that he thought

his

theory was better than the work of scientists who had made those

determinations. That strikes me a rather nervy. By

the way

I checked some of them and Mendeleev was right.

Here is a printed

version of his

table with some of the blanks filled in as the elements were

found. The second table shows some of his notes that helped

convince him that there were elements yet to be discovered.

I wasn't able to figure

out just what

this diagram was showing. There are 7 sectors with numbered

circles in them and lines connecting some of them. The

sectors

could correspond to the columns of the periodic table (minus the noble

gases which were unknown at that time) but the numbers don't seem to

match up with atomic weights. There are notations in Russian

that

would help to understand it I am sure but since I read Russian at an

early first grade level I will need some help. If you know

Russian or chemistry and would like to try just click the picture for a

high resolution version and then let me know what you figure

out.

The label at the bottom says something about a (logical topic/theory?

scheme) and I can't translate the rest.

Some of his chemicals on

display. I didn't try to read many of the labels but that

purple

one in the center says it is K Cl O4 which I think

should be a white

crystal. Maybe I missed a letter or two in the formula.

When I saw these I couldn't help thinking about the chemicals that were

in Edison's lab in New Jersey. Not long after I visited it,

many

years ago, they discovered there were many bottles of toxic and/or

potentially explosive chemicals there. I wonder if these have

been checked.

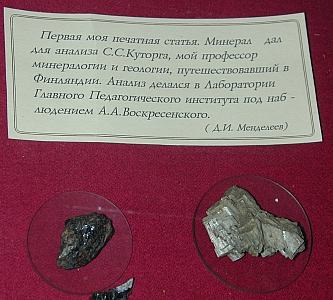

If you were doing

chemistry research

in the 1860's you may have been working with minerals to see if you

could isolate new chemicals and if you were very lucky or very good new

elements. How would you know if you had been

successful?

Only by checking the properties after you had purified it and comparing

those with all of those then known. The shape of the crystals

that are formed is one of those properties. Here we see 2

mineral

samples and 3 common crystal forms that were on display.

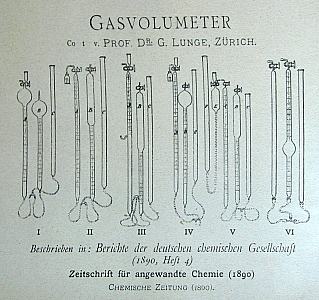

Equal volumes of gases

contain the

same number of atoms (if they are the same pressure and

temperature). This provides a way to compare the atomic

weight of

some elements. All we have to do is accurately measure the

volume, weight, temperature, and pressure of the element in

gaseous form. If they aren't gases maybe a compound of the

unknown with other already known elements is. Measure that

compound and do some arithmetic and you have the atomic weight of the

unknown. What if you can't find any compounds that are

gases. You could try to measure the amount of some material

that

you have already characterized it takes to completely react with your

unknown sample. If you do that accurately, and can figure out

the

chemical formulas for the reactants and the product, and measure the

weights of each, and do more arithmetic you have the atomic weight of

your unknown.

Simple, right!

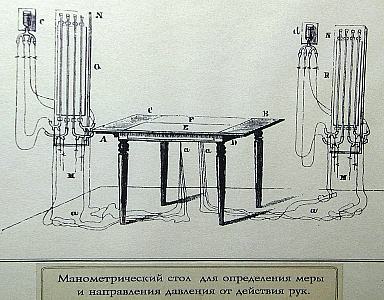

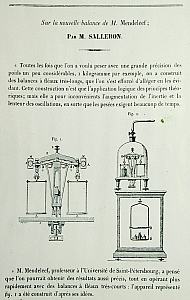

To do any of this you

used a lot of

precision apparatus. Glass tubes to hold the gases connected

to

other tubes of liquids so that pressures and volumes can be

measured. Scales (balances) of many types to permit you to

weigh

solids liquids and gases. Some of these were invented or

improved

by Mendeleev and their design was published, for some he followed the

designs of others.

I 'm not sure just what

this

apparatus is. My best guess is that it was used to separate

crude

oil into different fractions based on their volatility.

Some of the special

purpose glassware

on display.

Two balances.

The second was

used to compare the weights of equal volumes of gas. Because

the

glass containers are the same size they automatically compensate for

atmospheric buoyancy.

Two slow

pendulums. They may

have been used to measure equal time intervals so that reaction

kinetics could be studied.

The column of this

instrument had a

finely ruled scale. The device on it could be moved and its

height accurately determined. There was also what appeared to

be

a small telescope.

My best guess is that

this was used

to measure the change in the level of the liquid in the glass tubes

without requiring all of them to be scribed with scales. This

would ensure accuracy and save a lot of effort in the production of the

tubes.

This seemed to be a

transit minus the

telescope. I can't figure out just what it was used for in a

chemistry lab.

Here is Mendeleev's

office. We

saw reference books in Russian, French, German and other

languages. One in English was from the Franklin institute in

Philadelphia. Pictures of famous scientists were on the wall

behind him. A chess set was ready for a game and this glass

sphere tetrahedron was displayed on his desk.

Photography and painting

were

hobbies. Here is his camera and some of the pictures he

took. All photographers in those days were chemists but they

didn't have Mendeleev's expertise.

Mendeleev traveled

through much of

Europe and also the the United States. The map shows places

he

visited to teach, and to meet with other scientists to learn what they

had been working on.

His notebook entries

show some of the

places he visited in the US. The stop in Oil City was

especially

interesting to Nancy and I since it is only a few miles from where we

grew up.

A couple of bearded

scientists.

The one on the right is the famous one.

This little museum was a highlight of our trip to Russia.

If you want

more information

or can help me to understand more of what I saw I would like to hear

from you.

More

of our trip to Russia St.

Petersburg and Moscow

See other places we have

visited here.

<>Go

to our Personal

home page

Go to our Community

page

Go

to our Science

Fun page

E-mail Nancy

and

Alan